Vinmøte Lars Ivar 21. mars 2013

Nuits Saint Georges 2009, Tesco

Middels anonym nese med enkel rødbærsfrukt. Frisk og grei sommervin. Lett Pinot, noe grønn og får nok litt hjelp av årgangens rike stil. Men under kr. 200,- for en Nuits St. Georges er helt OK (£ 19.99) 85 poengChambolle Musigny 1cru Derrière la Grange 1993, Maison Roche de Bellene

Pen munnfølelse, holder seg veldig godt, frisk og grei. Litt kjemisk/grønn note. Lars Ivar prøvde å prate opp denne uten hell. Viser årgangens holdbare stil. 88 poeng.Pinot Noir 2010, Domaine Drouhin-Williamette Valley Oregon

Lilla, parfymerte sommerblomster, vulkansk, granittaktig, plommer, sjokolade og mye nyanser. Litt eksotisk med spontangjær-aktig nese og en deilig sådan. Kim sa dette ikke var Burgund, Roar veddet imot ! Kim var både i Beajoulais og i Rhone. Fjøsaktig, men fremdeles en ren og skarp, fin fruktprofil. En del fat med innslag av flosscandy/sukkertøy. 86-89 poeng.Chambolle Musigny 1990, Domaine Comte Georges de Vogue

Mørkere frukt med skogbunn, sopp og rosin. Tørr og skarp syre. Ikke en optimal flaske. Øyvind var i Piemonte/Barbaresco. Synd, dette skal være bra. 80 poeng.Fra burgundy-report:

It was around 1880 when the Côtes de Nuits village of Chambolle decided to improve its profile by appending the name of its most illustrious vineyard, thus to become Chambolle-Musigny. Despite this early attempt at marketing, Chambolle-Musigny has remained a working village rather than a place for tourists. Today, however, you will find two restaurants and a good hotel, though fifteen years ago all three were missing; there was once a vegetable shop too, but it didn’t last…

The village nestles in a small cleft at the base of a steep wooded hillside, the Combe de Chamboeuf. Through the centre of the village runs (mainly underground) the river Grône from which it is said the village takes it’s name: Though referred to as Cambola in the year 1110, it is believed that the name Chambolle derives from the regular bursting of the banks of the Grône during heavy rain, a ‘champ bouillant’ if you like.

Chambolle’s ancient church (monument historique) is worth a visit, some of the paintings here were bestowed by de Vogüé’s ancestors; if you enjoy the grisly art of the late middle-ages I can particularly recommend the painting of a scene from John the Baptist… The roads in the village are often narrow and winding; one such road follows the lower side of the church, part-way down you will meet an archway on the right-hand-side, an archway that will lead you into the 15th century courtyard of the Domaine Comte Georges de Vogüé, built by Jean Moisson in the 1400′s this has always been the home of the domaine.

The domaine – Past & Present

Many domaines in Burgundy can trace their roots back over 100 years, though since the majority of the vineyards were owned by the church and aristocracy until ~1790, only a handful of domaines can claim more than 200 years of history. The Domaine Comte Georges de Vogüé, however, can trace a line back over 550 years to ~1450 and the Chambolle vines of one Jean Moisson (as above). Today it is the 20th generation of the family that head the domaine; Claire de Causans and Marie de Ladoucette, the granddaughters of the late Comte Georges de Vogüé (1898-1987) who is pictured right. Comte Georges took over from his father Arthur in 1925, changing at that time the name of the domain from Comte Arthur to Comte Georges, though from around 1980 Comte Georges’ daughter, Elizabeth, took ever greater responsibility. Following the death of her father, it was she that decided to put a new team in place; Gérard Gaudeau tended the vines, though today that position is held (since 1996) by Eric Bourgogne – a most fitting name – Francois Millet was made responsible for the winemaking at the retirement of Alain Roumier, and in 1988 Jean-Luc Pépin, ex Domaine Joseph Drouhin, became responsible for the sales. For a short time before the arrival of Jean-Luc, Elizabeth’s son-in-law Gérard de Causans, husband to Claire, took the rôle of finance and sales, but was sadly cut-down in his prime by terminal illness.

De Vogüé and family Roumier

For many, many years a Roumier was instrumental in the work of the domaine. Alain Roumier was the régisseur for the domaine during the time of Comte Georges, as apparently was his father and grandfather before him. As reported by Robert Parker, it was Alain Roumier who famously suggested that if the wines of the seventies and eighties were not quite as good as before, then blame “Americans’ obsession with brilliant, clear wines” and the subsequent need for the domaine to filter. Of course, this being a family affair, it wasn’t just Alain that was involved; study the photo above of Comte Georges, and the man in the outsize beret and glasses to his right is Georges Roumier, uncle of Christophe from today’s Domaine Georges Roumier.

Working the vines – Eric Bourgogne walks you through the vineyards talking of the domaine’s philosophy; they practice ‘lutte raisonée’ (reasoned battle) which is effectively intervention only as required rather than treatment as prevention. Eric points out that in the challenging 2004 vintage (hail, oïdium, rot) they only sprayed six or seven times, most biodynamic domaines would have made double that number of treatments. In common with most domaines in Chambolle they also practice ‘confusion sexuelle’ – these are the small brown tags of insect pheromones that you see on the end of the rows of vines. Eric believes that a balance of insects is best, as treatments against one insect type will often have negative consequences for beneficial predators. Across the domaine Eric uses three types of pruning; Guyot, Cordon Royat and for the young vines a formation pruning.

Within Musigny, they now allow the weeds and grass to grow between the rows throughout the autumn and winter, ploughing by horse from Spring onwards, they use no weed killer. Eric believes that these choices result in less-compacted soil and significantly less erosion than the domaine used to experience. The domaine puts their own compost on the vineyards at a rate of 2 hectares per year, this translates to an addition of compost every six years. It’s very interesting when you look up the rows in Le Musigny, despite no difference in treatment, the grass between the rows suddenly stops as the vines change from mature pinot to young chardonnay. Something to do with shallow roots and less soil? – Who knows…?

A whiff of controversy

It comes with the territory; like Domaine de la Romanée-Conti and to a lesser extent also Domaine Leroy; the high prices asked for the wines set a certain level of expectation, add into the mix the overwhelming ownership of one of the most gifted terroirs and expectation is exponentially greater. As Matt Kramer said (Making Sense of Burgundy, 1989) the wine should “deliver the exhilaration one has a right to expect from Musigny”. In some ways it is even tougher for de Vogüé as there are other Musignys around to provide a benchmark, anyway we shouldn’t feel sorry for the domaine as they are in a fortunate and responsible position: It is, however, precisely because they are in such a position that so many people feel the need to pass judgement – some informed, some not. Today at least, if something needs to be done, it is done. The perfect example is what they did in 1991; a localised hail-storm ripped through Musigny, heading north until it stopped on the border with Morey St-Denis. Francois Millet’s quick pre-harvest vinification of the Musigny showed the taste of hail, so sixty people were used (it is said with tweezers) to remove every single damaged grape, and what a clean wine it is today.

Almost all commentators talk of a mid-1970′s to mid-1980′s dip in quality, so no smoke without fire but some seem reticent to accept that the ‘old quality’ – whatever that means – could once more be found in the wines of today. The 1990 Musigny is an interesting example: those that tasted from barrel saw greatness, those currently tasting from bottle are often underwhelmed, calling the wine Bordeauxesque. Without saying so directly, Francois Millet gently chides those that comment on the wine today, saying that ‘only those who tasted from barrel, know the true potential of that wine’. I find myself drawn to his viewpoint; all those great Musignys of the 40′s, 50′s and 60′s were proclaimed great when they were 30+ years old, the 1990 has plenty of time before it needs to ‘deliver’.

Summary

I think it is quite fair to comment on the constituent parts of young wines and indeed what we believe the future might hold for them but the real truth will be available to all only once they reach maturity. I see an exemplary quality to the domaine’s wines but there is also a linearity, a haughtiness, a slight lack of ‘warmth’ if you prefer. However you wish to describe it, relative their peers, there is a lack of charm in these young wines. I stress young, because the 1993 villages and the 1992 Amoureuses show both charm and character, perhaps then, it really is just a question of time. If that is the case, then an equally important question is: how do you know when the time is right? Both Francois and Jean-Luc are happy to emphasise – call and ask us – they keep enough half-bottles to test the wines from each vintage on a regular basis. I really should try and visit next time they open their 1990s…

It is never cheap to produce the best wine possible, that said, the domaine’s wines have always been priced above most pockets. I believe that in the 1990s the wines excel in the context of each vintage but if you consider that an average 1993 is significantly better than an average 1992 or 1994 then it’s also possible to point to a spectacular lack of value in ‘lesser’ vintages, but I’m convinced that they are worth every penny in the good vintages – which happens to be most of the last 15+ years. I’m sure my 1999′s could outlive me, though of course, I’d be disappointed if they had the opportunity…

The history of Musigny

Gaston Roupnel

The only ‘Tête de Cuvée’ reported in Chambolle by Dr Lavalle (1855), Musigny lies at an altitude between 260 and 300 metres, sitting just above the Clos de Vougeot and Chambolle-Musigny Les Amoureuses. The vineyard is relatively flat at it’s junction with the road to the east (at least in Les Musigny) but quickly rises with an incline of around 10° to it’s western boundary. Below the soil is a mix of Bathonian and Bajocian bedrock – limestone – this limestone is particularly hard (unlike the limestone in de Vogüé’s Bonnes-Mares) causing many fissures as water freezes in it’s cracks. Given the depth of the local quarries this bedrock could be as deep as 200 metres. Walk up-slope about one-third of the way into the vineyard and there is around 40cm of soil covering the rocky base, walk another third in the same direction and there is as little as 20cm of soil.

One suggestion for the origin of the vineyard’s name comes from a Gallo-Roman name – Musinus . Others suggest that it came from a prominent family by the name of Musigny who was recorded as having lived in Burgundy at the time of the Ducs of Burgundy. Anthony Hanson (Burgundy, revised 1999) points to the earliest record of the vineyard dating from 1110 “when the Canon of Saint-Denis de Vergy, Pierre Cros, gave his field of Musigné to the monks of Citeaux”. There is also cause for confusion; before the French Revolution there was also a sub-climat within the Clos de Vougeot called Les Petits Musigny – presumably the part now called Musigni – we can only guess what the current ‘Les Petits Musigny’ was called at that time…

A selection of wines were drunk and compared on two separate days; the first a January dinner in London organised by the, then, newly appointed UK agents for de Vogüé, Corney & Barrow, and the second, for the 2000 vintage reds, on a cold February day at the domaine in Chambolle-Musigny.

Musigny Blanc to bourgogne blanc

It is the location that is classed as Grand Cru, so red or white (assuming the AOC is in place), if the grapes come from Musigny the resulting wine is entitled to the Musigny label. Robert Parker (Burgundy, 1990) wrote that the Chardonnay vines of Musigny were “planted at the request of the late Comtesse de Vogüé”; at the domaine today there is no direct evidence of that, or an exact planting date, but what is sure is that there was definitely a white Musigny produced as early as the 1930′s, so the Comtesse would have been quite young for making such a ‘request’. Today ‘only’ a Bourgogne blanc is produced, but potentially this is the only Grand cru white from the Côte de Nuits; though in the the nineteenth century it was also possible to find Chambertin blanc but the vines were already gone when AOC rules were introduced in the 1930s, hence, no AOC is now in place therefore Chambertin blanc is no-longer allowed. This white wine of Musigny is made from chardonnay vines sited, in two plots, right at the top of the Musigny vineyard. Because there is no such AOC as Chambolle-Musigny Blanc (villages or 1er Cru) if the Musigny Grand Cru label is not used, it follows that the wine must be declassified all the way down to Bourgogne (blanc). The 2000 vintage comes from a plot of 0.4 ha, the average age of these vines is currently 14, there are still some vines of 40-45 years but the majority were replanted in 1986, ’87 and ’91. There is also an additional plot of 0.2 ha which was replanted in 1997. The domaine doesn’t yet see sufficient depth and complexity from these vines for the Musigny label, this is despite legally requiring only three years from planting to using a Grand Cru label. They feel that the 2000 wine is some way between a village and a 1er, though 2001 & 2002 in their opinion is firmly at 1er cru quality. Around 20% new wood is typically used for this wine’s elevage, a mere 100 cases per year trickle into the market.Chambolle-Musigny premier cru

Despite owning portions of Les Baudes and Les Fuées in addition to their holding in Amoureuses, there is actually no premier cru wine in these bottles, only the declassified juice from the young (under 25 years) Musigny vines – Musigny in short trousers as the domaine likes to call it. The first outing for this wine was the 1995 vintage – before this time quite a lot of juice was sold to the negociants and bore a Musigny label. Today there are about 2.8 hectares of these young vines, producing around 500 cases of Chambolle-Musigny 1er Cru per year.Chambolle-Musigny 1er Cru Les Amoureuses

The highest part of the Amoureuses vineyard is separated from Musigny by a small road, it is here that the domaine’s 0.56 ha holding is located. The vines average 31 years-old and produce a mere 160 or-so cases per vintage.Bonnes-Mares Grand Cru

The domaine owns a block of vines accounting for 2.7 hectares and an average production of ~420 cases per year. The vines are located entirely in the Chambolle portion of the vineyard that is closest to the village itself, this provides for a slightly more elegant Bonnes-Mares, but one that is heavily scented with violet and peony. The domaine’s vines average 29 years old.

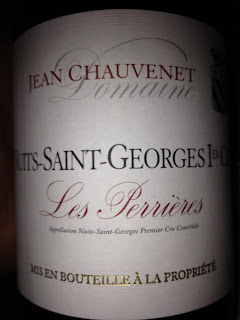

Nuits-Saint-Georges 1cru Les Perrieres 2009, Domaine Jean Chauvenet

Frisk Pinor med strøk av pepper i finish. Mørk, litt varm, mye krydder. 89 poengDescription

Christophe Draag, son-in-law of Jean Chauvenet has taken the lead of the domaine . Wines tend to be powerful in their youngness and not easy to appreciate but give them some time and you will rediscover the real pleasure of top Bourgogne from the Côte de Nuit. €49.60

La Porta di Vertine 2008, Chianti Classico

Mørk og brunelloaktig. Tett, frisk, lakris og fatpreget finish. 86 poengAbout the wine: This is the first vintage in which Sangiovese fruit was harvested from the Colle ai Lecci property and blended into the wines. The vineyards at Colle ai Lecci have a large proportion of old vines (40 years and older) producing minute quantities of very concentrated grapes.

After the arrival of the grapes into the cellar the fruit was destemmed but not crushed. This delays the beginning of fermentation and creates more regular and lower temperatures, an important factor, as the fruit is fermented without any temperature control. Fermentation is triggered by indigenous yeast and without any addition of sulphur. Remontage with aeration was used in the first couple of days to help start fermentation, and obtain good color extraction. The wine remained on the skins for three to four weeks, after which it was racked off into 25 hl old casks and tonneaux. The wine stayed on the fine lees without any racking or movement until the following harvest, after which it was racked off and transferred back into cask for another 8 months of ageing. After bottling the wine was estate cellared for an additional year. Grape variety: Sangiovese, Canaiolo, Colorino, Pugnitello

Ingen kommentarer:

Legg inn en kommentar